How to Treat Heat-Related Illness in Backyard Chickens.

While cold weather issues often take precedence in the minds of backyard chicken keepers, heat-related illnesses are usually more deadly to backyard flocks. Unlike cold weather bringing snow and ice, hot weather is more dangerous than cold and wet weather combined. Dehydration and heat stroke can decimate a flock in minutes if proper precautions are not taken to avoid these issues.

In this post, I will discuss how soaring summer temperatures affect chicken physiology and how to avoid, treat, and prevent heat-related illnesses.

Chicken Physiology, Body Plan, and Dehydration:

Related to the mighty Tyrannosaurus Rex, chickens are theropods and can trace their lineage back to the common ancestor of dinosaurs. (Brusatte, 2018).

All birds – chickens included – are dinosaurs. Specifically, birds are a type of theropod rooted in the dinosaur family tree that contains the same ferocious meat-eaters as T-Rex and Velociraptor (Brusatte, 2018).

Birds perch within an advanced group of dinosaurs called paravians – a subgroup of a theropod that traded in the brute body plan of their gargantuan ancestors for larger brains, sharpened acute senses, and smaller, lighter bodies that permitted progressive lifestyles above their land-dwelling relatives. Anatomically, chickens have many common characteristics that define the body plan of these magnificent creatures.

Chickens and all birds have a unique body plan visible in the skeleton. Comparing the skeleton of Tyrannosaurus Rex with modern chickens yields similar anatomical attributes. T-Rex has a skull attached to a spine, ribs, and two legs with splayed toes, providing swift bipedal locomotion. Focusing on the appendicular skeleton, we see that T-Rex and modern chickens have an S-shaped skeleton. The reason is that body plans do not have unlimited parts from which evolution can choose but rather build upon earlier ancestral shapes (Horner, 2009).

While it’s easy to say that these features are of birds, they are not attributes of birds at all but of dinosaurs.

Like the nightly T-Rex, chickens are related to saurischians – the line of the dinosaur family tree that contains both the giant sauropods and theropods – possessed skeletal pneumaticity – spaces for air in their bones.

Skeletal pneumaticity produces hollow bones that lighten the skeleton, allowing for a wide range of motion. Without pneumaticity, sauropods would be unable to lift their long necks, and giant theropods would lack the agility and ability to run because their skeletons would be far too heavy.

In birds, air sacks are an ultra-efficient lung oxygen system. This flow-through inhalation and exhalation provide the high-energy birds need during flight. Evolving one hundred million years before birds took flight, this is the true secret to their ability to take to the skies.

While pneumaticity is an incredible anatomical adaption inherited from their ferocious ancestors, it also makes birds vulnerable to dehydration. In warm weather, this ultra-efficient lung oxygen system requires access to water for optimal performance. In backyard chickens, readily available water is crucial to prevent dehydration. In extreme heat, chickens can dehydrate fast, causing compromised health and death.

Preventing dehydration in backyard chickens is crucial in hot weather. Water needs to be accessible at all times and if free-ranging in multiple locations. In my backyard, I have multiple waterers suspended from red Shepard hooks.

When free ranging a backyard flock, it is necessary to keep water in easy reach from several locations. If the only water source is at a distance chickens can dehydrate before they can access water.

Electrolytes:

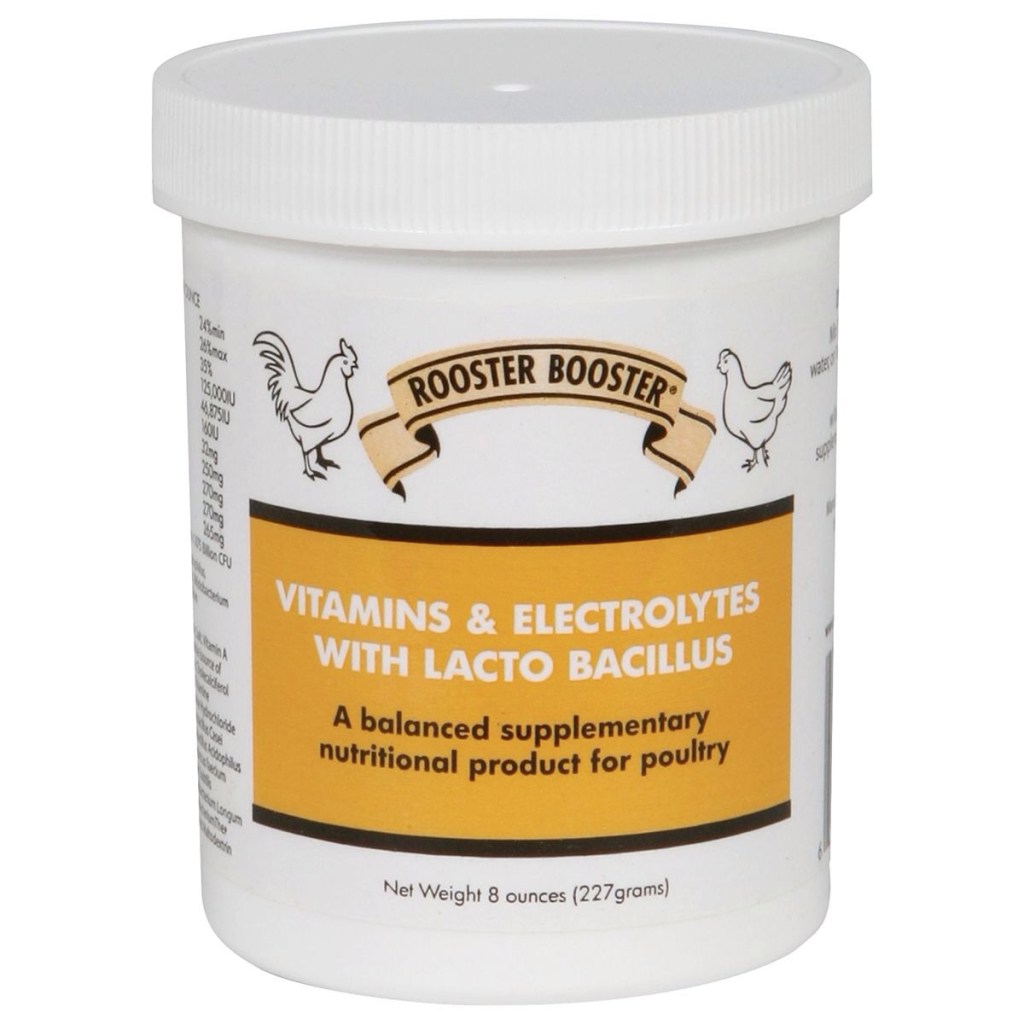

Like Gatorade for humans, electrolytes are necessary for optimal flock health in hot weather. When temperatures soar, I add electrolytes to my flock’s water daily. Following package instructions for administration, electrolytes for poultry will aid in supporting the chicken’s body providing proper hydration.

Shade:

Whether in the coop/pen or free-ranging, shade is key for optimal flock health in hot weather. In allowing the flock to free range in a backyard, plant pushes or trees that provide shade from the hot afternoon sun. If the free ranging area is too small, simple canopy tents are a great alternative.

In my backyard, I have multiple areas providing shade for the flock. I also post watering stations near these locations to help the flock stay hydrated while they rest in the shade.

Provide Chicken A/C:

Another trick of the trade is to provide your flock chicken A/C. During the hottest part of the day, use a hose to saturate a favorite shaded spot for the flock. The water will cool the ground and the chickens will rest on the cool ground acting as A/C that will help the flock stay cool. If your property allows, placing a misting host on the ground will also provide this cooling effect. The chickens will come and go out of the mist as needed depending on individual comfort levels.

Treating Heat Illness in Backyard Flocks:

The signs of heat illness in chickens are much the same in humans. Lifelessness, exhaustion, lack of appetite, pale comb, dry mouth, passing out, and death.

If you notice any of the above symptoms in a flock member, immediate action is required. The first measure is to take the heat-affected individual to water. Many times, the heat-stressed bird needs quick access to water. If the individual is strong enough to drink, this will quickly rectify the situation. Keep the ill individual near the watering source in a pen or shaded location to recover.

If the heat illness is more severe, direct administration may be necessary. Using a syringe with the needle removed, provide water mixed with electrolytes directly to the affected flock member. When given orally, the patient will drink the water, providing relief.

Note of caution: do NOT force the water down their throat; chickens have a passage in the back of their mouth that leads directly to the lungs. Instead, slowly administer the water and allow the bird to drink the water.

I have a video on my YouTube Channel demonstrating the correct oral administration using Wormer. While this video focuses on worming a backyard flock, the oral methodology is the same. The skills here can be extrapolated and transferred to heat-related illnesses in backyard chickens.

If possible, isolate the heat-stressed member to a cool shaded place such as a laundry room, mud room, or shaded location in the pen, and over several hours, administer water in small doses to help the member recover from the heat-related illness.

Most chickens treated for heat stress in this manner make a full recovery and no ill health is observed.

I hope this post has helped treat a heat-stressed backyard flock. Like cold weather challenges, hot weather has associated risks that need to be addressed to have a happy and healthy backyard flock. If you have any questions feel free to reach out, by leaving a comment or dropping me an email at kuntryklucker@gmail.com

I am a multi-disciplinary writer, blogger, and online content creator. If you like this post, please visit my online writing portfolio or other sites.

Coffee and Coelophysis – A blog about dinosaurs!

Introvert Cafe – A mental Health blog.

As always, thanks for reading. Till next time, keep on crowing!

~ The Kuntry Klucker Crew ~

Resources:

Brusatte, Steve. The Rise and Fall of the Dinosaurs: A History of Their Lost World. William Marrow of Harper Collins Publishers. New York, NY. 2018. Pts. 270.

Horner, Jack. How to Build a Dinosaur. Plume, Published by Penguin Group. London, England. 2009. Pts. 8,9.